At such pandemic proportions, violence against women is a serious global health threat and public policy problem.

Violence increases women's vulnerability to many social and health problems, including depression, alcohol use disorders, unsafe abortions, pregnancy related complications, and STIs, including HIV.

Importantly, intimate partner violence against women is a significant cause of death and injury. Particularly in resource-poor settings and low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), many factors work against women and lead to staggering rates of death, injury, and disability from violence.

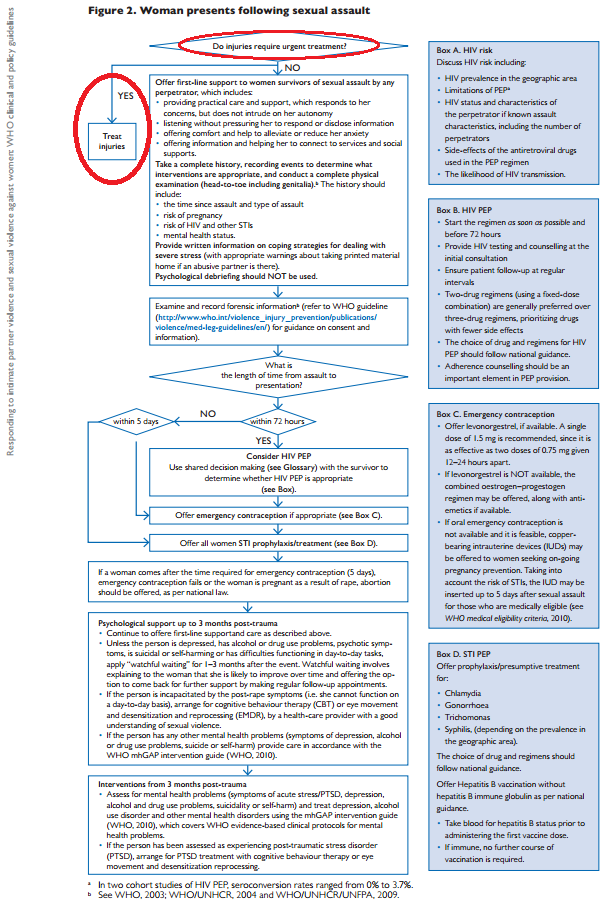

The WHO report offers detailed recommendations for health providers on what to do after a woman that has experienced violence presents to them at their clinic.

The report's Figure 2 summarizes these recommendations, beginning by asking the health provider to assess whether the woman is presenting with injuries that require urgent treatment. If her injuries do, indeed, require urgent treatment, the report recommends the health provider's next step, which is simply: Treat injuries.

|

| Source. |

That's it.

The WHO report just stops there. It seems to assume that women in resource-poor, often remote, settings in LMICs actually have access to trained health providers and health facilities with the capacity to treat their injuries. This is seriously problematic.

A recent review on the "Care of the Injured Worldwide" by Sakran et al explains the realities on the ground:

- Surgical disease, which includes traumatic injury, is among the top causes of death and disability worldwide.

- Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death under the age of 45 in the US and worldwide.

- These traumatic injuries account for 10% of the world's deaths, more than the number of deaths from malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS combined.

The world's poorest people, and among them, marginalized women, particularly those vulnerable women that are victims of violence, face the greatest barriers to accessing life-saving emergency and essential surgical care.

According to Sakran et al and others, the reasons why this is the case boils down to a lack of effective political advocacy and insufficient investment in training frontline health providers and building infrastructure and capacity in primary health facilities, perhaps due to erroneous perceptions that providing emergency and essential surgical interventions are too expensive or complex by population-based measures, even though the World Bank and others have determined promoting surgery to be a cost-effective, life-saving treasure in low-income countries.

The WHO's clinical and policy guidelines report responding to violence against women has gotten tremendous attention by mass media, health providers, and policymakers around the globe. People are feeling the urgency of addressing violence against women, as they should.

It is just unfortunate that the WHO report neglected to offer guidelines on how health providers and policymakers in low-resource settings should actually go about treating and saving women from pandemic-levels of death and disability from violence.

In order to protect women and prevent such astounding morbidity and mortality, clinical and policy guidelines to respond to violence against women can not just focus on prevention, mental health services, and STI management. All of these are important, of course, but equipping frontline health providers with the training and tools to detect and best treat women that experienced injuries from violence is also a critical component, particularly necessary to care for women that are becoming victims at this very minute.

Just as treating patients with AIDS is as important as preventing the transmission of HIV, treating the acute needs of women that are victims of violence is as important as preventing violence against women.

If 42% of women experience injuries as a result of physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner, and 38% of all murders of women globally are reported as being committed by their intimate partners, should WHO not recommend equipping health facilities that are most accessible to women at risk with the skilled health providers, emergency equipment, and capacities necessary to save their lives? To care for their wounds, burns, life-threatening injuries? To prevent and reduce disability?

Violence against women in many parts of the world often goes unrecognized, underreported, and neglected, particularly in low-resource settings that do not have adequate emergency and essential care capacities at primary or first-referral health centers to care for women experiencing violence, or anyone else, for that matter. Women that experience violence in these settings may not turn to law enforcement or other domestic violence-specific services or centers, whether they are near or far.

Since victims are most likely to interact with the health system for acute health needs, health providers are in the unique position to identify abuse and intervene before serious injury or death occurs. The WHO report recommendations also acknowledge that "as much as possible should be done during first contact, in case the woman does not return. Follow-up support, care, and the negotiation of safe and accessible means for follow-up consultation should be offered." Frontline health providers, like those in the emergency room or ones at primary or first-referral health facilities in LMICs, are an important contact with the victims of domestic violence, and timely identification and intervention can save lives.

The WHO report notes: "Ideally, women experiencing partner violence should be identified at the point of contact with health services, although these settings are not always conducive to providing such services." Perhaps it is true that these health settings are not "conducive to providing such services" right now, but it's imperative for the WHO and partners to support health ministries in building health systems that are suited to address violence against women and other emergency and primary care health issues.

Where is the WHO recommendation to build the capacity for emergency and essential trauma, surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia/resuscitation services for these women in primary, first-referral health centers?

Women must be able to access care and services at their most physically-accessible, first-referral health centers, where they are most likely to show up with acute needs after experiencing violence. This is why, in low-resource settings, first-referral health facilities are considered the optimal starting point for effective management of injury. These emergency or primary health centers are also more easily able to integrate care and provisions for women experiencing violence into their routine patient care and clinic services.

If the evidence shows that it's best to integrate emergency and essential surgical care, first-line and continued supports, emergency contraception, and STI laboratory and treatment services into primary, first-referral health facilities to address violence against women, where is the WHO recommendation urging the integration of these comprehensive services into LMICs' national health plans?

By neglecting to recommend or even note the importance of ensuring women's access to emergency and essential trauma and surgical care at first-referral health centers, the WHO missed a major opportunity to have a significant impact on policymakers interested in improving the care and lives of mothers, wives, daughters, sisters, and everyone related to them, particularly in ways that fit into their ongoing efforts to strengthen their national health plans and systems.

At the 66th World Health Assembly last month, I attended a panel with health ministers and representatives from Belgium, India, Mexico, Zambia, the USA, and the Netherlands on Addressing Violence Against Women. As mentioned in a previous post, each panelist briefly shared general progress and interest in addressing violence against women in their respective countries. Health ministry leaders' commitment to address violence against women is particularly important for building the momentum for real change on the ground.

Efforts to comprehensively address violence against women must be integrated into national health plans and social policies across sectors. Building the infrastructure (such as laboratory services and essential equipment/medicines supply chain) and capacity (such as training frontline providers to manage injuries, burns, and resuscitation) to deliver accessible acute care and support services to women that have experienced violence requires political leadership and financial investment. Delivering appropriate emergency services to survivors of violence at first-referral health facilities in resource-poor areas should be an integral component of a national health ministry's health systems strengthening agenda and budget. Strengthening emergency care systems and capabilities for local health facilities to serve women that are victims of violence requires political commitment from all levels.

Perhaps it is not politically correct for me to say this, but I write from my humble intern's perspective -- I am deeply disappointed that there is not more collaboration and communication among the many WHO programs/departments/units. I'm not sure what it will take, but this report brings light to one of the most important issues of our time, one that is particularly personally important to me. It is just unfortunate because the program with which I'm interning within the WHO, the Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) Program, would have easily been able to help support and fill major gaps in the report's clinical and policy recommendations.[2]

The Director General of the WHO, Dr. Margaret Chan, said in a recent statement, "We see that the world's health systems can and must do more for women who experience violence." Indeed, it is time we all do more to support health systems in caring for women.

---

[1] "About the report: The report was developed by WHO, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the South African Medical Research Council. It is the first systematic review and synthesis of the body of scientific data on the prevalence of two forms of violence against women – violence by an intimate partner and sexual violence by someone other than an intimate partner. It shows for the first time, aggregated global and regional prevalence estimates of these two forms of violence, generated using population data from all over the world that have been compiled in a systematic way. The report documents the effects of violence on women’s physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health. This was based on systematic reviews looking at data on the association between the different forms of violence considered and specific health outcomes." Source.

[2] The WHO EESC Program works directly with ministries of health in LMICs and other partners to advocate for leaders' commitment to a cross-cutting approach rooted in national health planning. The program focuses on integration of emergency medicine and essential surgical care, which includes caring for victims of domestic violence, into first-referral level, primary health care facilities, and the WHO EESC Program's Integrated Management for EESC toolkit includes the Emergency Trauma Care workshop and other useful tools for health providers and policymakers. Reducing death and disability from domestic violence is also a priority for WHO GIEESC members. If you are interested in partnering and collaborating to achieve quality, safe emergency and surgical care for people living in low-resource settings, I'd encourage you to consider joining the WHO GIEESC community today. Also, the 5th Biennial Meeting for the WHO GIEESC will take place on October 14-15, 2013 in Trinidad and Tobago. Registration is free of charge.

The WHO's clinical and policy guidelines report responding to violence against women has gotten tremendous attention by mass media, health providers, and policymakers around the globe. People are feeling the urgency of addressing violence against women, as they should.

It is just unfortunate that the WHO report neglected to offer guidelines on how health providers and policymakers in low-resource settings should actually go about treating and saving women from pandemic-levels of death and disability from violence.

In order to protect women and prevent such astounding morbidity and mortality, clinical and policy guidelines to respond to violence against women can not just focus on prevention, mental health services, and STI management. All of these are important, of course, but equipping frontline health providers with the training and tools to detect and best treat women that experienced injuries from violence is also a critical component, particularly necessary to care for women that are becoming victims at this very minute.

Just as treating patients with AIDS is as important as preventing the transmission of HIV, treating the acute needs of women that are victims of violence is as important as preventing violence against women.

If 42% of women experience injuries as a result of physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner, and 38% of all murders of women globally are reported as being committed by their intimate partners, should WHO not recommend equipping health facilities that are most accessible to women at risk with the skilled health providers, emergency equipment, and capacities necessary to save their lives? To care for their wounds, burns, life-threatening injuries? To prevent and reduce disability?

Violence against women in many parts of the world often goes unrecognized, underreported, and neglected, particularly in low-resource settings that do not have adequate emergency and essential care capacities at primary or first-referral health centers to care for women experiencing violence, or anyone else, for that matter. Women that experience violence in these settings may not turn to law enforcement or other domestic violence-specific services or centers, whether they are near or far.

Since victims are most likely to interact with the health system for acute health needs, health providers are in the unique position to identify abuse and intervene before serious injury or death occurs. The WHO report recommendations also acknowledge that "as much as possible should be done during first contact, in case the woman does not return. Follow-up support, care, and the negotiation of safe and accessible means for follow-up consultation should be offered." Frontline health providers, like those in the emergency room or ones at primary or first-referral health facilities in LMICs, are an important contact with the victims of domestic violence, and timely identification and intervention can save lives.

The WHO report notes: "Ideally, women experiencing partner violence should be identified at the point of contact with health services, although these settings are not always conducive to providing such services." Perhaps it is true that these health settings are not "conducive to providing such services" right now, but it's imperative for the WHO and partners to support health ministries in building health systems that are suited to address violence against women and other emergency and primary care health issues.

Where is the WHO recommendation to build the capacity for emergency and essential trauma, surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia/resuscitation services for these women in primary, first-referral health centers?

Women must be able to access care and services at their most physically-accessible, first-referral health centers, where they are most likely to show up with acute needs after experiencing violence. This is why, in low-resource settings, first-referral health facilities are considered the optimal starting point for effective management of injury. These emergency or primary health centers are also more easily able to integrate care and provisions for women experiencing violence into their routine patient care and clinic services.

If the evidence shows that it's best to integrate emergency and essential surgical care, first-line and continued supports, emergency contraception, and STI laboratory and treatment services into primary, first-referral health facilities to address violence against women, where is the WHO recommendation urging the integration of these comprehensive services into LMICs' national health plans?

By neglecting to recommend or even note the importance of ensuring women's access to emergency and essential trauma and surgical care at first-referral health centers, the WHO missed a major opportunity to have a significant impact on policymakers interested in improving the care and lives of mothers, wives, daughters, sisters, and everyone related to them, particularly in ways that fit into their ongoing efforts to strengthen their national health plans and systems.

At the 66th World Health Assembly last month, I attended a panel with health ministers and representatives from Belgium, India, Mexico, Zambia, the USA, and the Netherlands on Addressing Violence Against Women. As mentioned in a previous post, each panelist briefly shared general progress and interest in addressing violence against women in their respective countries. Health ministry leaders' commitment to address violence against women is particularly important for building the momentum for real change on the ground.

Efforts to comprehensively address violence against women must be integrated into national health plans and social policies across sectors. Building the infrastructure (such as laboratory services and essential equipment/medicines supply chain) and capacity (such as training frontline providers to manage injuries, burns, and resuscitation) to deliver accessible acute care and support services to women that have experienced violence requires political leadership and financial investment. Delivering appropriate emergency services to survivors of violence at first-referral health facilities in resource-poor areas should be an integral component of a national health ministry's health systems strengthening agenda and budget. Strengthening emergency care systems and capabilities for local health facilities to serve women that are victims of violence requires political commitment from all levels.

Perhaps it is not politically correct for me to say this, but I write from my humble intern's perspective -- I am deeply disappointed that there is not more collaboration and communication among the many WHO programs/departments/units. I'm not sure what it will take, but this report brings light to one of the most important issues of our time, one that is particularly personally important to me. It is just unfortunate because the program with which I'm interning within the WHO, the Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) Program, would have easily been able to help support and fill major gaps in the report's clinical and policy recommendations.[2]

The Director General of the WHO, Dr. Margaret Chan, said in a recent statement, "We see that the world's health systems can and must do more for women who experience violence." Indeed, it is time we all do more to support health systems in caring for women.

---

[1] "About the report: The report was developed by WHO, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the South African Medical Research Council. It is the first systematic review and synthesis of the body of scientific data on the prevalence of two forms of violence against women – violence by an intimate partner and sexual violence by someone other than an intimate partner. It shows for the first time, aggregated global and regional prevalence estimates of these two forms of violence, generated using population data from all over the world that have been compiled in a systematic way. The report documents the effects of violence on women’s physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health. This was based on systematic reviews looking at data on the association between the different forms of violence considered and specific health outcomes." Source.

[2] The WHO EESC Program works directly with ministries of health in LMICs and other partners to advocate for leaders' commitment to a cross-cutting approach rooted in national health planning. The program focuses on integration of emergency medicine and essential surgical care, which includes caring for victims of domestic violence, into first-referral level, primary health care facilities, and the WHO EESC Program's Integrated Management for EESC toolkit includes the Emergency Trauma Care workshop and other useful tools for health providers and policymakers. Reducing death and disability from domestic violence is also a priority for WHO GIEESC members. If you are interested in partnering and collaborating to achieve quality, safe emergency and surgical care for people living in low-resource settings, I'd encourage you to consider joining the WHO GIEESC community today. Also, the 5th Biennial Meeting for the WHO GIEESC will take place on October 14-15, 2013 in Trinidad and Tobago. Registration is free of charge.

No comments:

Post a Comment